Spring 2024: The Lady Garden, explained

Stella McCartney’s Spring 2024 collection seeks inspiration from the Lady Garden; an empowering sanctuary where women can exist without societal expectations, as well as the metaphorical term for feminine anatomy.

Throughout history, the connotations surrounding female anatomy and femininity as a whole have consistently fluctuated from good to bad, or from sacred to satanic.

To Stella, the Lady Garden represents a likeminded community with friendship, sisterhood and the planet at heart.

In history…

In ancient Mesopotamia – a region we now know as Iraq – the Sumer civilisation worshipped a goddess named Inanna. Associated with love, beauty and fertility, Inanna was typically depicted nude with hymns dedicated to her that celebrated sexuality and the sacredness of the vulva.

Ancient Egyptians also revered fertility, as well as sexuality. The hieroglyphic symbol for the vulva, often referred to as the "knot of Isis," represented the goddess Isis and the magical concept of life. Similarly, Roman culture associated the vagina with fertility and motherhood – the goddess Venus, for example, was linked to love, beauty, and procreation.

In contrast, ancient Greeks rarely depicted female genitalia in art. Instead, there were references to the vagina in plays and literature indicating it was both feared and desired. However, the main shift in how female bodies, sexuality and sensuality were perceived happened during the 5th – 15th century in Medieval Europe. Christianity led to the idolisation of The Virgin Mary, her purity becoming most desirable and anything falling short of that – including the vagina – was labelled as sinful or shameful.

Following this period, the Renaissance saw a revival of interest in classical art and literature. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael (alongside hundreds more) took a great interest in depicting human anatomy with great accuracy in art, but societal views towards the female form and sexuality remained complex.

Instead of progressing from this point, the Victorian Era that followed was a strictly moral and suppressive period. Modesty was of utmost importance and to even discuss topics such as sex or genitalia was seen as shockingly uncouth.

Two hundred years go by, and the Sexual Revolution begins; attitudes towards sexuality shift, traditional views are challenged and discussions surrounding these ‘taboo’ topics become open and active. This era paved the way for many of the artists, writers and activists we admire today to be able to work with the levels of freedom of expression that they do.

In art…

The Wall of a Thousand Vulvas and Sheela Na Gig

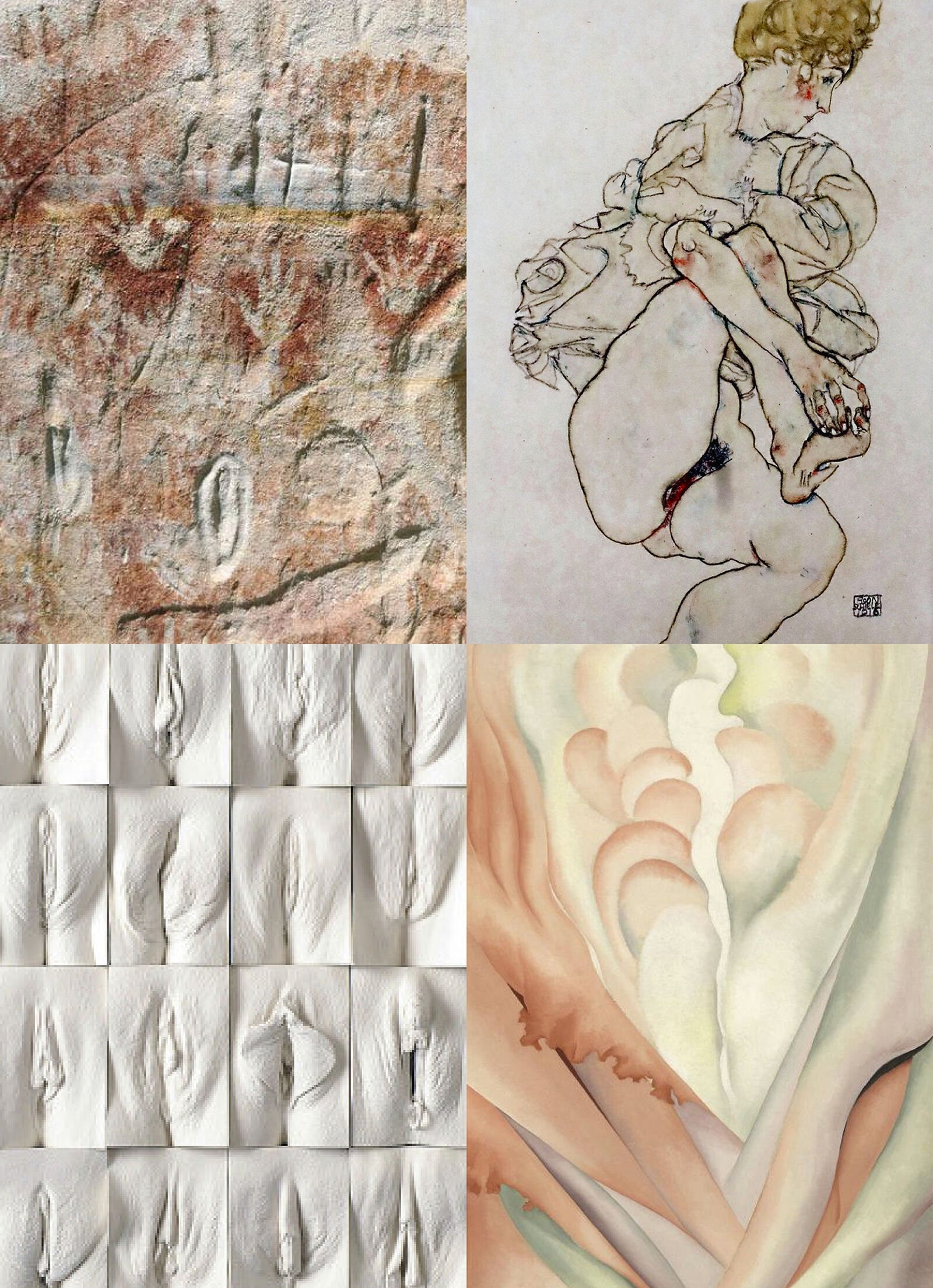

Representations of feminine anatomy crop up even in prehistoric art – such as in The Wall of a Thousand Vulvas in Queensland, Australia. The artefact lies in a gorge, boasting over a thousand vulva-shaped symbols that were carved into a stoneface by the first aboriginal community to settle there.

Sheela Na Gigs are another example: Gargoyle-like carvings of naked female figures displaying exaggerated vulvas. These can be found across Europe, the majority located in Ireland, and are thought to date back to the 11th century.

Though it’s uncertain what these works represent, it’s largely accepted that they indicate a reverence towards women and fertility.

Egon Schiele and Jamie McCartney

Depictions of nakedness and genitalia have been an artistic mainstay throughout history, peaking and pitting in popularity over the years but never going extinct. Austrian artist Egon Schiele’s work acts as an example of the female form illustrated through a male gaze, providing some of the most savage, revolutionary and liberating nude works produced in his time.

More recently, Jamie McCartney gave us The Great Wall of Vaginas. Using plaster casts, he made ten panels of moulds showcasing the genitalia of identical twins, transgender individuals, pregnant women and pre-labiaplasty patients – showing audiences what normal women really look like.

Hannah Wilke and Judy Chicago

Naturally, an increase in femininity-championing art occurred during the 60s. Hannah Wilke was a feminist artist whose sculptural works concentrated on the vulva and opted for materials such as terracotta, latex, erasers and even chewing gum to convey her visions. In a 1980 issue of Art News, Wilke was quoted saying “I chose gum because it’s the perfect metaphor for the American woman – chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece.”

Another example of feminism in artistry is Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party”: A large-scale installation on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum. It depicts a long table with three-dimensional plate settings that pay tribute to some of the most influential women in Western civilization…and their nether regions.

In media…

Feminist Movement

Though there’s still work to be done, feminism has played a crucial role in redefining perceptions of the vagina – especially in the 20th and 21st centuries – with discussions about body autonomy, reproductive rights, and sexual empowerment becoming commonplace.

Not only are these subjects central to feminist discourse, but they have led to legal changes being made in favour of women’s health on a global scale.

Pop Culture, Social Media and Activism

While it can also do the exact opposite, contemporary media often challenges traditional narratives, promotes body positivity, inclusivity and celebrates the diversity of female bodies.

Similarly, though social media platforms can be a toxic place, they also provide a space for open discussions about the female body, challenging taboos and contributing to the broader conversation on women's health and empowerment.

Cultural Diversity

As with anything and everything, different cultures have diverse perspectives on the female body; some celebrate the vagina as a symbol of life and fertility, and others may have more conservative views.

It's important to note that attitudes towards the vagina vary widely across cultures and historical periods, and these generalizations may not capture the full complexity of individual perspectives.

Additionally, societal views continue to evolve, influenced by ongoing discussions around gender, sexuality, and women's rights.